Google searches for "Price of bread in China" are referring people to this blog more and more frequently, so I'm going to take a moment out for an off-topic post that will hopefully provide some insight into that question. First I'll explain why it's actually the wrong question to ask, and then I'll take two different cracks at answering it anyway for those of you who are still curious.

It is my experience that usually, when someone refers to the price of bread, it's an example of the rhetorical device synecdoche. Thus, to just look at one example, when Berio writes in his Sinfonia that the piece of music can't stop the wars or lower the price of bread, it is simply meant to stand in for food in general. The device works because bread is a staple food in Europe and plays a very prominent role in the diet. Even if meat is too expensive, you fall back on bread.

China has a very different dietary model, however. Baked goods do not play a large role in the diet, and bread is not regularly eaten by the average Chinese person. Instead, depending on the region, rice and noodles fill that role. If you're interested in using one item to stand for the entire Chinese diet, I suggest considering the cost of rice instead. To consider the price of bread in China is like looking at the price of corn in England -- not particularly relevant or helpful.

So, then, how much does food cost in China? It's a huge, economically diverse country, so there isn't a nice, simple answer. It's a lot more expensive in Shanghai than it is Gansu, for example, where you can get a good meal for 3 yuan. Just as a hamburger in New York will cost you a lot more than the same burger in Kansas, specific prices vary wildly throughout the country. That said, my understanding is that the uncharacteristically snowy winter has put a lot of pressure on food supplies throughout the entire country, so food is becoming more expensive everywhere.

And even though I just explained why the price of bread in China isn't relevant, I'll tell you about it anyway. For the reasons I just outlined, bread tends to be very expensive and low in quality. For whatever reason, the domestic bread producers like to put a lot of sugar in the bread. I have no idea what they leave out, but it tastes sweet and has a somewhat chalky texture. It could perhaps make a serviceable piece of toast provided you use enough jam. I preferred yoghurt, fruit, or eggs for breakfast.

There is one institution that ironically provides a decent loaf of bread for cheap. In my experience, the European-owned supermarkets that feature a variety of imported foods could bake a decent French- or Italian-style loaf, for about a third of the price of the terrible packaged bread.

Edit 4/16: PRI's The World on the topic of Chinese food prices

Showing posts with label China. Show all posts

Showing posts with label China. Show all posts

2.27.2008

1.28.2007

1 + 1 = 1.3

My favorite formula is now 1 + 1 = 1.By combining elements of Western music learned in conservatory and traditional Chinese music he learned growing up in rural Hunan province, Tan Dun's goal is to create a new, unified music that is neither Eastern nor Western. As such, I think that is the standard by which the opera should be judged: how well did it accomplish what the composer set out to do?

-Tan Dun

While I've long been a fan of Tan Dun, I have very little exposure to his operas. (I've heard the songs from "The Peony Pavilion" included on the album "Bitter Love," but have almost no sense of how it fits together as an opera. I don't know any of the music from Marco Polo or Tea.) The piece that most successfully synthesizes the musical styles is his 2000 Water Passion after St. Matthew. (Ironically, a passion setting is such a strictly Western form; there is no Chinese analogue for the religious oratorio.) He is able to integrate the Eastern folk tradition's emphasis on indeterminate pitch and techniques of using natural objects and throat singing into a moving telling of the death and resurrection of somebody else's savior. While Bach's setting of the same story inspired and influenced him, it comes through as a new and unique music. It is both Chinese and American, and yet neither at the same time. 1 + 1 = 1.

Unfortunately, The First Emperor is a step back. It is best when it stays in the framework of Tan's previous works. It opens with a masterly aria by the Taiwanese Peking opera star Wu Hsing-Kuo that is, unfortunately, the high point of the entire opera. The best of the remaining music is the interludes, where he lets the orchestra (and percussionists) cut lose. It is particularly strong when featuring the zheng (a Chinese zither), the waterphone, the Chinese ceremonial bell, and other instrumental specialties.

Where it falls short is what happens in between. It seems that Tan is almost trigger shy about his formulation of 1 + 1 = 1, and thus doesn't fully commit. While I can sympathize with his desire to take full advantage of a cast headlined by Placido Domingo, much of the singing falls into an almost dull Western arioso style. It isn't the Tan Dun I admire so; it's Tan Dun interspersed with Puccini. Tan became a great composer by exploring, and so many parts of the opera were content to just sit in a traditional lyricism.

Still, on the balance, it was an enjoyable opera. If I have any reservations, it's because my expectations were so high (despite the dozens of negative reviews). I hope that he will tighten act II a little and tone down the Westerness of the vocal lines prior to recording the work. Still, I anticipate taping the PBS broadcast and watching it over the air as many times as possible.

With such a predominantly Chinese creative team (ex-pats Tan, Ha Jin, and Hao Jiang Tian in addition to Zhang Yimou, Fan Yue, Huang Doudou and Wang Chaoge), I was curious to see what the opera's theme would be. Despite his early outsider films, Zhang Yimou's recent work has served as propaganda for the Chinese government. (The unity theme of "Hero" seems a clear enough statement to the Taiwanese, Tibetan, and Uyghur separatists; even Curse of the Golden Flower is about the importance of order and obeying authority.) I am pleased that The First Emperor's stands against the communist government, highlighting Qin's cruelty. In particular, the act of suppressing the old art for a new, truthful art was played out all too often during the tragic Cultural Revolution. And, as happens in the opera, suppressive government can lead to art more interested in exploring the truth than the government line. Gao's national anthem may as well have been Tan's own Snow in June.

Labels:

China,

New music,

Opera,

Passion Settings

1.04.2007

The Great Kinkades of China

Like the Mongols of the twelfth century, today's bloggers have breached the Great Firewall. Which is to say, I discovered last night that China is allowing foreign blogs to be read (at least, at the moment). I may as well take advantage of this opportunity and try to write some more about China, for my readers over there. Coincidentally, there's something good to write about in the paper this morning:

The Times discusses the recent trend in Chinese art: selling your work for millions of yuan. At first glance, this would seem to aid the artistic process in China, but does it really?

The problem is that when the focus becomes economic, then the art suffers. This may not have been a concious strategy by the government to protect itself from satire, but it's working wonders by bringing these artists into the fold, and moving their focus to money. The question is no longer what Zhang Xiaogang [张晓刚] has to say about China during the Cultural Revolution; it's how many new versions of that same painting of the family of three his studio can churn out and sell. Who cares what Fang Lijun [方力钧] thinks about the post-Tiananmen world. How many paintings or sculptures of distorted faces can he finish in time for the next auction?

It's as if the artists of China are collectively turning from the Pollocks, Rothkos, and Warhols into many Thomas Kinkades, using "art" as a way to print money, expression be damned.

I realize that this is an overly bleak assessment; I look forward to a new generation of artists who will come shine some light on this problem by finding a way around it. I fear that it's too late for the current generation, though.

The Times discusses the recent trend in Chinese art: selling your work for millions of yuan. At first glance, this would seem to aid the artistic process in China, but does it really?

The problem is that when the focus becomes economic, then the art suffers. This may not have been a concious strategy by the government to protect itself from satire, but it's working wonders by bringing these artists into the fold, and moving their focus to money. The question is no longer what Zhang Xiaogang [张晓刚] has to say about China during the Cultural Revolution; it's how many new versions of that same painting of the family of three his studio can churn out and sell. Who cares what Fang Lijun [方力钧] thinks about the post-Tiananmen world. How many paintings or sculptures of distorted faces can he finish in time for the next auction?

It's as if the artists of China are collectively turning from the Pollocks, Rothkos, and Warhols into many Thomas Kinkades, using "art" as a way to print money, expression be damned.

I realize that this is an overly bleak assessment; I look forward to a new generation of artists who will come shine some light on this problem by finding a way around it. I fear that it's too late for the current generation, though.

Labels:

China,

Visual Art

3.30.2006

The Best Chinese Food in New York (With No Chinese Necessary)

The hand-pulled noodles on the left are from Cafe Kashkarin Brooklyn.

The hand-pulled noodles on the left are from Cafe Kashkarin Brooklyn.It's one of the few places outside of mainland China where it's possible to get genuine lagman (拉面 in Chinese).

I should clarify that the stir-fried noodles above are half-eaten, which is why it looks a little skimpy. To me, it tasted just like the 炒面 I got in the little noodle shops I ate in throughout China.

As much as I'd like the picture to be the story here, the only way to really get the story is to find your way out to 1141 Brighton Beach Boulevard. It takes forever to get there from Manhattan, but it's well worth the trek. (It's not quite as far as China, after all.)

Labels:

China

3.05.2006

"...or lower the price of bread"

Whenever children find out that I lived in China, the first thing they always ask is what strange foods I ate. Did I eat monkey brains? Dog meat? Bugs?

Adults also tend to be interested in food, but the question is always how the Chinese food compares to the restaurants here. (My stock response? "Over there, they just call it food.") I always go into the same speech: that the kind of food I enjoyed the most, and ate almost every day, isn't available in America. I enjoyed the Uyghur Muslim food. The food has a strong emphasis on lamb and fresh hand-pulled noodles. The farther West you travel in China, the better this food gets (although it is available pretty much anywhere in China proper). The real center of this food universe is Lanzhou, the capital of Gansu province, which lends its name to the noodle shops in the rest of the country. When I took my trip around the country, I strongly considered taking a food pilgrimage there.

Accordingly, I was very interested to read of the economic crisis developing in Lanzhou, where a number of factors have lead from noodle prices increasing 2.2 yuan to 2.5. (Funny how economies work; even in Jinan, a bowl of noodles cost 3 yuan.)

Adults also tend to be interested in food, but the question is always how the Chinese food compares to the restaurants here. (My stock response? "Over there, they just call it food.") I always go into the same speech: that the kind of food I enjoyed the most, and ate almost every day, isn't available in America. I enjoyed the Uyghur Muslim food. The food has a strong emphasis on lamb and fresh hand-pulled noodles. The farther West you travel in China, the better this food gets (although it is available pretty much anywhere in China proper). The real center of this food universe is Lanzhou, the capital of Gansu province, which lends its name to the noodle shops in the rest of the country. When I took my trip around the country, I strongly considered taking a food pilgrimage there.

Accordingly, I was very interested to read of the economic crisis developing in Lanzhou, where a number of factors have lead from noodle prices increasing 2.2 yuan to 2.5. (Funny how economies work; even in Jinan, a bowl of noodles cost 3 yuan.)

Labels:

China

2.25.2006

Folk sounds, both Eastern and Lower-Eastern

I had only a week left in China, that night I was sitting at the center of Xian, killing time before heading off to the train station for the overnight train to Chengdu. I was across the rotary from the illuminated bell tower. There was a busker was playing folk songs on an erhu. At that point, I wished I had some sort of sound recorder. I reflected on all the sounds I'd wanted to record during my time in China, like the bizarre music at the underground McDonalds in Jinan's Quancheng Square or the KFC across from the Bank of China in Wuxi, the cries of the pushcart vendors, and the opera teacher who lived in the flat below me in Jinan.

I had particular regrets about one evening in Nanjing. My friend Cissy took me to Jiming Si when I visited for the weekend. We arrived shortly before they closed the gates for the evening. We did the normal things you do at a Chinese monestary. We climbed to the top of the pagoda (which has the beautiful view of the city walls and the Yangtze River pictured right). As we were about to leave, about thirty monks filed into the main temple in the complex. I suggested to Cissy that we wait around and see what they would do. They lined up in rows. One stepped aside and started hitting a bell. The rest started chanting. It reminded me a bit of Medieval organum, but it was a totally new sound that I had never heard before.

My friend Cissy took me to Jiming Si when I visited for the weekend. We arrived shortly before they closed the gates for the evening. We did the normal things you do at a Chinese monestary. We climbed to the top of the pagoda (which has the beautiful view of the city walls and the Yangtze River pictured right). As we were about to leave, about thirty monks filed into the main temple in the complex. I suggested to Cissy that we wait around and see what they would do. They lined up in rows. One stepped aside and started hitting a bell. The rest started chanting. It reminded me a bit of Medieval organum, but it was a totally new sound that I had never heard before.

From that day on, I searched tirelessly for a recording of this sort of Buddhist chant, to no avail. The Buddhist recordings I was able to find were more influenced by Western new age music than anything from traditional Buddhist liturgy. (The theory goes that Buddhism has new-age appeal in America, so accordingly anything with new-age influence will sell to tourists, authenticity be damned.) When I was in Xian -- the same day that I found that busker -- I found what I was looking for. One of the gift shops inside of Dayan Ta was playing that music -- not the same chant, I'm sure, but the same kind of music. I asked them which CD it was, and the clerk apologized, explaining that it wasn't for sale. They only had one copy, but they recommended that I buy one of the many other CD's of Buddhist chant. I sampled them, and they were all wrong. That was the only time I ever pulled the "I'm an American, your feeble currency has no value to me!" trick the entire time I was gone. For the amount of money I paid them, I could have gotten one copy of every CD they had. It was fine; I finally got my chant.

Of course, that was just one sound -- as for the rest, they won't be recovered. Perhaps one day I'll return to China with the sound recorder and capture all those sounds. Maybe I'll even take a page from Tan Dun and The Map and try to seek out local folk musics.

The New York Tenament Museum has a wonderful project right now that focuses on the recorded sounds and folk music of the very diverse Lower East Side. You can make your own musique concrète with sounds from the city. They're working on features that will allow you to save your pieces and listen to others', and upload your own sounds if you have any. Hear the project first-hand at Folksongs for the Fivepoints.

I had particular regrets about one evening in Nanjing.

My friend Cissy took me to Jiming Si when I visited for the weekend. We arrived shortly before they closed the gates for the evening. We did the normal things you do at a Chinese monestary. We climbed to the top of the pagoda (which has the beautiful view of the city walls and the Yangtze River pictured right). As we were about to leave, about thirty monks filed into the main temple in the complex. I suggested to Cissy that we wait around and see what they would do. They lined up in rows. One stepped aside and started hitting a bell. The rest started chanting. It reminded me a bit of Medieval organum, but it was a totally new sound that I had never heard before.

My friend Cissy took me to Jiming Si when I visited for the weekend. We arrived shortly before they closed the gates for the evening. We did the normal things you do at a Chinese monestary. We climbed to the top of the pagoda (which has the beautiful view of the city walls and the Yangtze River pictured right). As we were about to leave, about thirty monks filed into the main temple in the complex. I suggested to Cissy that we wait around and see what they would do. They lined up in rows. One stepped aside and started hitting a bell. The rest started chanting. It reminded me a bit of Medieval organum, but it was a totally new sound that I had never heard before.From that day on, I searched tirelessly for a recording of this sort of Buddhist chant, to no avail. The Buddhist recordings I was able to find were more influenced by Western new age music than anything from traditional Buddhist liturgy. (The theory goes that Buddhism has new-age appeal in America, so accordingly anything with new-age influence will sell to tourists, authenticity be damned.) When I was in Xian -- the same day that I found that busker -- I found what I was looking for. One of the gift shops inside of Dayan Ta was playing that music -- not the same chant, I'm sure, but the same kind of music. I asked them which CD it was, and the clerk apologized, explaining that it wasn't for sale. They only had one copy, but they recommended that I buy one of the many other CD's of Buddhist chant. I sampled them, and they were all wrong. That was the only time I ever pulled the "I'm an American, your feeble currency has no value to me!" trick the entire time I was gone. For the amount of money I paid them, I could have gotten one copy of every CD they had. It was fine; I finally got my chant.

Of course, that was just one sound -- as for the rest, they won't be recovered. Perhaps one day I'll return to China with the sound recorder and capture all those sounds. Maybe I'll even take a page from Tan Dun and The Map and try to seek out local folk musics.

The New York Tenament Museum has a wonderful project right now that focuses on the recorded sounds and folk music of the very diverse Lower East Side. You can make your own musique concrète with sounds from the city. They're working on features that will allow you to save your pieces and listen to others', and upload your own sounds if you have any. Hear the project first-hand at Folksongs for the Fivepoints.

Labels:

China

1.03.2006

鲍元恺,祝你生日快乐

I purchased my first contemporary classical Chinese cd by accident.

Near the beginning of my year in China, I found a CD of the Long Yu and the Chinese Philharmonic Orchestra playing Schoenberg and Wagner. They did a fine job with the decidedly European selections. I didn't think much more about it for a long time.

When I got home, I listened to the disc on my computer. Something very bizarre happened. Instead of automatically playing, it opened a folder. What was in this folder? Mp3's of another China Philharmonic Orchestra CD, this time playing the music of Bao Yuankai, Wang Ming, and other Chinese composers of the past 50 years.

Today (at least by Beijing time), Bao turns 61. I'm very happy to (accidentally) know who he is and have some of his music.

Near the beginning of my year in China, I found a CD of the Long Yu and the Chinese Philharmonic Orchestra playing Schoenberg and Wagner. They did a fine job with the decidedly European selections. I didn't think much more about it for a long time.

When I got home, I listened to the disc on my computer. Something very bizarre happened. Instead of automatically playing, it opened a folder. What was in this folder? Mp3's of another China Philharmonic Orchestra CD, this time playing the music of Bao Yuankai, Wang Ming, and other Chinese composers of the past 50 years.

Today (at least by Beijing time), Bao turns 61. I'm very happy to (accidentally) know who he is and have some of his music.

Labels:

China,

World music

12.30.2005

Behind the Great Firewall

I did something rare and difficult: I got my blog read in China (at least by one person). (See the proof here.) My friend Rena helped me gather some of the photos of some of the ugly Chinese sculptures, so I wanted her to see those entries. She's very intellegent and very open-minded (which is a rare quality in the people I met over there, so I feel like I actually can discuss things with her.

She pointed out two sculptures in Tiananmen Square, which have very famous within China. Of the first, Rena writes, "but that soldier sculptures are considered as one of the greatest sculptures after 1949 P.R. China set up in the text book." (Forgive her English, which, all things being equal, is actually very strong, though far from perfect.) As an outsider, it's hard to be enthusiastic about what is actually a pretty straightforward piece of propaganda, all content and no form. Yes, we get it, the communists were heroic and saved China. I don't really take anything from this sculpture, though, as art. There is a more interesting sculpture, across the street in front of Tiananmen proper. It is a marble pillar [华表], traditionally placed in front of palaces and tombs. When I reacted positively to the pillar, Rena had an interesting reaction:

anything from this sculpture, though, as art. There is a more interesting sculpture, across the street in front of Tiananmen proper. It is a marble pillar [华表], traditionally placed in front of palaces and tombs. When I reacted positively to the pillar, Rena had an interesting reaction:

She raises an interesting question: to what extent is it possible to retain a Chinese identity without just repeating the past again and again? Is it possible to incorporate Western ideas while still being Chinese?

This is actually a much greater issue, which has played out repeatedly throughout the history of music. American composers faced the same struggles with the influences of European music. Conventional wisdom has it that it wasn't until the turn of the 20th century that Charles Ives solved that problem (though I think people don't give William Billings full credit). Russia had its own conflict in the second half of the nineteenth century. (For that matter, look at the wave of nationalistic composers who felt compelled to assert their own countries' musical autonomies throughout the century.)

The problem is particularly strong in China, however, because of its history. From the end of the nineteenth through the first half of the twentieth century, there was a strong foreign presence in certain areas. Suddenly, after the revolution, that ended. The next twenty five years featured strict isolation, until foreign influences were gradually allowed again. The result is a country that today is still struggling to find a voice. (I'm glossing over a lot of issues for the sake of length, although those may come up in future posts.)

It's encouraging to talk to Rena and know that she struggles with these questions, as a young citizen of the country. It's not just up to the artists to find an identity.

She pointed out two sculptures in Tiananmen Square, which have very famous within China. Of the first, Rena writes, "but that soldier sculptures are considered as one of the greatest sculptures after 1949 P.R. China set up in the text book." (Forgive her English, which, all things being equal, is actually very strong, though far from perfect.) As an outsider, it's hard to be enthusiastic about what is actually a pretty straightforward piece of propaganda, all content and no form. Yes, we get it, the communists were heroic and saved China. I don't really take

I know foreigners always think these traditional things are much chinese. China is supposed to be like Xi'an

China should be full of old buildings with wing roofs

She raises an interesting question: to what extent is it possible to retain a Chinese identity without just repeating the past again and again? Is it possible to incorporate Western ideas while still being Chinese?

This is actually a much greater issue, which has played out repeatedly throughout the history of music. American composers faced the same struggles with the influences of European music. Conventional wisdom has it that it wasn't until the turn of the 20th century that Charles Ives solved that problem (though I think people don't give William Billings full credit). Russia had its own conflict in the second half of the nineteenth century. (For that matter, look at the wave of nationalistic composers who felt compelled to assert their own countries' musical autonomies throughout the century.)

The problem is particularly strong in China, however, because of its history. From the end of the nineteenth through the first half of the twentieth century, there was a strong foreign presence in certain areas. Suddenly, after the revolution, that ended. The next twenty five years featured strict isolation, until foreign influences were gradually allowed again. The result is a country that today is still struggling to find a voice. (I'm glossing over a lot of issues for the sake of length, although those may come up in future posts.)

It's encouraging to talk to Rena and know that she struggles with these questions, as a young citizen of the country. It's not just up to the artists to find an identity.

Labels:

China,

Visual Art

12.27.2005

The Art of the Public Square

My first day in Jinan, as my roommate took me on a tour of the city, he pointed out the large blue sculpture in the center of Quancheng Square. "All Chinese cities have them," he told me. The sculpture is a little bizarre, to say the least: two blue posts, seemingly made of fiberglass, which twist around a metallic globe in the center. In some ways, it's an exemplary giant Chinese public square sculpture. Based on just this picture, it isn't entirely clear what it is, or what it is meant to represent (other than Jinan's greatness that the city could build such a monument to itself). Although some of these sculptures are truly abstract, they tend to be abstractions of the square they sit in. But how do you represent a public square? In Jinan's case, it's pretty easy. 泉城广场 means "City of Springs Square," after one of Jinan's old names. Accordingly, you color the sculpture blue and show its components gushing from the ground to represent a spring. (Just try to ignore the fact that all but twelve of Jinan's 200 springs were paved over to build this square and its surrounding areas. Who needs a natural heritage when you have sculptures?)

My first day in Jinan, as my roommate took me on a tour of the city, he pointed out the large blue sculpture in the center of Quancheng Square. "All Chinese cities have them," he told me. The sculpture is a little bizarre, to say the least: two blue posts, seemingly made of fiberglass, which twist around a metallic globe in the center. In some ways, it's an exemplary giant Chinese public square sculpture. Based on just this picture, it isn't entirely clear what it is, or what it is meant to represent (other than Jinan's greatness that the city could build such a monument to itself). Although some of these sculptures are truly abstract, they tend to be abstractions of the square they sit in. But how do you represent a public square? In Jinan's case, it's pretty easy. 泉城广场 means "City of Springs Square," after one of Jinan's old names. Accordingly, you color the sculpture blue and show its components gushing from the ground to represent a spring. (Just try to ignore the fact that all but twelve of Jinan's 200 springs were paved over to build this square and its surrounding areas. Who needs a natural heritage when you have sculptures?)Most public squares in China, though, don't have names as evocative as "City of Springs."

How do you depict Civilization Square, for example? The solution used in this sculpture in Jiangyin, a small city in Jiangsu Province on the southern banks of the Yangtzi River, is to depict the word civilization itself. The Chinese word -- 文明 -- has two components. The 文 is unmistakable. (I'm not certain of this, but I believe that the version shown in the picture is in Chinese seal script.) 明 itself consists of two different characters: 日, meaning sun, and 月, meaning moon. Furthermore, texts in Chinese are traditionally can be written top to bottom. This sculpture is just the name of the square written large. (It is also a fitting sentiment for the front of the city government building. Google images has some other photos that give a good sense of its placement.)

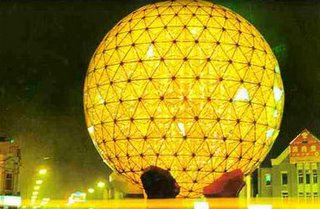

How do you depict Civilization Square, for example? The solution used in this sculpture in Jiangyin, a small city in Jiangsu Province on the southern banks of the Yangtzi River, is to depict the word civilization itself. The Chinese word -- 文明 -- has two components. The 文 is unmistakable. (I'm not certain of this, but I believe that the version shown in the picture is in Chinese seal script.) 明 itself consists of two different characters: 日, meaning sun, and 月, meaning moon. Furthermore, texts in Chinese are traditionally can be written top to bottom. This sculpture is just the name of the square written large. (It is also a fitting sentiment for the front of the city government building. Google images has some other photos that give a good sense of its placement.) Not all the sculptures are able to make such a connection, however. Dalian's Zhongshan Square, named after Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the founder of modern China, chooses a glowing orb as its centerpiece. The round sculpture is fitting for the center of Dalian's giant rotary at the center of the city. As you can see, at night, it lights up the square around it. (Or, at least the center of the square -- the edges of the square are lit up by the adjacent billboards and buildings.) However, it's hard to get excited about a sculpture whose chief influence is Epcot Center.

Not all the sculptures are able to make such a connection, however. Dalian's Zhongshan Square, named after Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the founder of modern China, chooses a glowing orb as its centerpiece. The round sculpture is fitting for the center of Dalian's giant rotary at the center of the city. As you can see, at night, it lights up the square around it. (Or, at least the center of the square -- the edges of the square are lit up by the adjacent billboards and buildings.) However, it's hard to get excited about a sculpture whose chief influence is Epcot Center.

Strange as it may sound, these are some of the normal ones. Consider the People's Square in Qinhuangdao. Legend has it, the great emporer Qin Shihuang went there seeking immortality. It is also the the point where the Great Wall reaches the sea. (More recently, it is the largest port in Hebei province since Tianjin left to become an independent municipality.) The square doesn't choose to explore the city's history, though, and the result is a very forgettable sculpture. There is little to distinguish it from its counterpart in People's Square in Linyi, a small city in southeastern Shandong Province. The Mayor of Linyi boasts of the city's heritage as the home of ancient manuscripts of Sun Tsu's Art of War and great figures from China's history. (Notice how the sculpture is used as the web sites

icon -- they are choosing it to be the symbol for the city.)

icon -- they are choosing it to be the symbol for the city.)What's the difference between these sculptures, though? They share the same Chinese red color, the same tripod structure, and the same jagged edges. An argument could be made that Qinhuangdao's version focuses itself inward, whereas Linyi's pushes outward, but that's a bit of a stretch. There is nothing to connect one to Qinhuangdao and the other to Linyi -- they could easily be swapped, and the cities would be no better or worse for it.

These sculptures are a uniqely Chinese phenomenon. I'd like to conclude with a picture of the mother of them all: the earliest such sculpture. This one is made of iron, in the far western city of Bali [巴黎, not to be confused with Bali in Indonesia]:

(See also photo supplement)

Labels:

China,

Visual Art

12.18.2005

NAMOC

One of the most interesting museums I visited in China was the National Art Museum of China (or NAMOC for short) [中国美术馆]. It offers a look at the last century of Chinese art. Needless to say, the twentieth century in China was one of great upheaval. That is reflected in the art.

One of the most interesting museums I visited in China was the National Art Museum of China (or NAMOC for short) [中国美术馆]. It offers a look at the last century of Chinese art. Needless to say, the twentieth century in China was one of great upheaval. That is reflected in the art.Yi Ming's [佚名] painting from 1928, is a good example of early Republican era art. In some ways it is two things at once -- it both fits in the tradition Chinese landscape painting and betrays European influences. Instead of the sparse Chinese textures, it is a full-scale oil painting. (The museum labels it as 仕 女肖像, which means "Portrait of Female Official." That is obviously not correct. You can see the actual female official here.)

As the civil war between the KMT and the CCP heated up, political themes became more

common. The struggles got worse with the invasion of Japan in 1937. "The Call of July 7" [“七七”的号角], painted by Tang Yihe [唐一禾] in 1940, depicts Chinese citizens marching to rebuff the Japanese. (This painting is very tame, actually. Take a look at the other paintings from the 1940's, which depict fighting, evacuations, and hunger.) The war, which didn't end until Japan surrendered to the US in 1945, is still a very current issue in Sino-Japanese relations. (It even has currency in the arts -- Bright Sheng, a Chinese composer now living in Michigan, wrote Nanking! Nanking!, a concerto about the Japanese occupation of Nanjing, in 1999.)

common. The struggles got worse with the invasion of Japan in 1937. "The Call of July 7" [“七七”的号角], painted by Tang Yihe [唐一禾] in 1940, depicts Chinese citizens marching to rebuff the Japanese. (This painting is very tame, actually. Take a look at the other paintings from the 1940's, which depict fighting, evacuations, and hunger.) The war, which didn't end until Japan surrendered to the US in 1945, is still a very current issue in Sino-Japanese relations. (It even has currency in the arts -- Bright Sheng, a Chinese composer now living in Michigan, wrote Nanking! Nanking!, a concerto about the Japanese occupation of Nanjing, in 1999.)After Mao declared the People's Republic in 1949, the tone of the paintings changed decidedly.

There was a resurgence of traditional style painting, consistent with the communist ideology's cultural

isolation. Naturally, there was also a surge in propaganda painting. The bucolic scene seems harmless enough, until you examine the iconography. Those peasant women, smiling as they plow the fields, are in traditional Tibetan dress. They are pleased because the enlightened Chinese occupying army has freed them from their own self rule. The painting's title? The First Step on the Golden Road [初踏黄金路]. Li Huanmin [ 李焕民] painted it in 1963, eleven years after Tibet was "liberated."

isolation. Naturally, there was also a surge in propaganda painting. The bucolic scene seems harmless enough, until you examine the iconography. Those peasant women, smiling as they plow the fields, are in traditional Tibetan dress. They are pleased because the enlightened Chinese occupying army has freed them from their own self rule. The painting's title? The First Step on the Golden Road [初踏黄金路]. Li Huanmin [ 李焕民] painted it in 1963, eleven years after Tibet was "liberated."Not all Chinese propoganda art is this cruel, however. Portraits of Mao were naturally quite popular, depicting him as a friend, a sage, an older brother, and, of course, as a wise leader. (These paintings still have currency in China today. Somehow, Mao has avoided the re-examination that brought Hitler and Stalin out of favor after they died.) My favorite of these is Sun Zixi's [孙滋溪] In Front of Tiananmen [前天安门], depicting a cross-section of Chinese citizens posing in front of the Gate of Heavenly Peace, China's national symbol. (The gate is across the street from Tiananmen Square, which has become infamous outside of China after the 1989 incident.)

The scene is one that is repeated hundreds (if not thousands) of times every day, as people from all over the country flock to see the monument that has been at the center of Chinese life for 500 years. In this painting, soldiers, officials, and peasants all stand together, along with people representing several of China's ethnic

The scene is one that is repeated hundreds (if not thousands) of times every day, as people from all over the country flock to see the monument that has been at the center of Chinese life for 500 years. In this painting, soldiers, officials, and peasants all stand together, along with people representing several of China's ethnic minorities. This is classical propoganda, showing the ideal society that communism (and Mao) have brought.

minorities. This is classical propoganda, showing the ideal society that communism (and Mao) have brought.The repressive Cultural Revolution years are conspicuously absent from the museum. The revolution sought to eliminate old customs, old habits, old thinking, and old culture. (That was communism at its worst.) Things started to open up then, however. Nixon visited and Deng Xiaoping instituted reforms, and Western influences returned to Chinese painting. There is little to suggest that this nude figure is a Chinese painting, or was painted in 1980. Jin Shangyi [靳尚谊] seems influenced by a classical Western sense of beauty. Likewise, Wei Qimei's [韦启美] New Wires [新 线 ] seems almost abstract (even though it depicts something very concrete -- large spools of electircal wire demonstrating China's modernization). The texture of the paint almost takes over from the images on the canvas.

I'm going to artificially stop this brief survey at 1983. At some point, I'll pick things back up and include a look at Shanghai's gallery, which has a better collection of contemporary art. Also planned is a look at contemporary Chinese classical music, which shares a similar trajectory as painting. Finally, I'll be doing the first assessment of an important genre of modern Chinese sculpture: the art of the Chinese public square.

For more on painting, check out the on-line collections of the National Art Museum of China and the Shanghai Art Museum. Don't be intimidated by the Chinese writing; just click around on things and have fun.

Labels:

China,

Visual Art

12.15.2005

A Dam Strange Symphony

When the Chinese government displaces millions of people and submerges one of its great natural wonders to build a giant dam, what's a composer to do?

Glorify it through a symphony.

Liu Yuan's [刘湲] Echo from the Three Gorges depicts the massive construction project now going on up the Yangtze River from Chongqing. It is the latest result of his collaboration with the Xiamen Philharmonic Orchestra (read in English or Chinese). Don't get me wrong; I think the orchestra's heavy emphasis on contemporary Chinese composers is a good thing (as it should be). Very few composers in China have achieved international fame of any level (Tan Dun being the most famous by far). However, it's hard to make much sense of this piece.

I searched around a bit for Liu's music, and was able to drum up a piece called Shadier's Legend [沙迪尔传奇], played by the Traditional Music Orchestra at Renmin University, conducted by Yang Chunlin. Shadier is a Uighur peasant who inspired people to struggle through his song. He was killed by his enemies. Can you believe that the same composer who chronicles the life and death of a hero who struggled against an oppresive government is writing about the miracle of a terrible construction project?

(When is the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority to announce the BSO is premiering the Big Dig symphony next season?)

Glorify it through a symphony.

Liu Yuan's [刘湲] Echo from the Three Gorges depicts the massive construction project now going on up the Yangtze River from Chongqing. It is the latest result of his collaboration with the Xiamen Philharmonic Orchestra (read in English or Chinese). Don't get me wrong; I think the orchestra's heavy emphasis on contemporary Chinese composers is a good thing (as it should be). Very few composers in China have achieved international fame of any level (Tan Dun being the most famous by far). However, it's hard to make much sense of this piece.

I searched around a bit for Liu's music, and was able to drum up a piece called Shadier's Legend [沙迪尔传奇], played by the Traditional Music Orchestra at Renmin University, conducted by Yang Chunlin. Shadier is a Uighur peasant who inspired people to struggle through his song. He was killed by his enemies. Can you believe that the same composer who chronicles the life and death of a hero who struggled against an oppresive government is writing about the miracle of a terrible construction project?

(When is the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority to announce the BSO is premiering the Big Dig symphony next season?)

Labels:

China

12.13.2005

Incipit vita nova

Dal mio Pernesso amato a voi ne vengo,

Incliti eroi, sangue gentil de regi,

Di cui narra la Fama eccelsi pregi,

Ne giunge al ver perch'e alto il segno.

Senior year of high school, my music theory special topics teacher gave me a long list of music to listen to. I listened to the two excerpts featured in the Norton Antholog of Western Music: La Musica's prologue and Orfeo's aria "Tu se morte." I was unimpressed; the only note I wrote was "Same ritornello every time." (Funny that a ritornello should be repeated.) At that point, I was more interested in dense Wagner scores than baroque opera.

Years later, I moved to China for a year, and had a chance to learn about Chinese classical music. I discovered one of the interesting qurks of history: L'Orfeo, the first great European opera, was written 9 years after the greatest Chinese opera, 牡丹亭 (The Dream of the Peony Pavillion). The stories are remarkably similar. Both involve a man who brings his lover back to life. Orpheus uses his legendary songs to win over Pluto, only to lose her when he thinks she has left him for one moment. Tang Xianzu tells a classic Chinese tale, of lovers who meet in a dream. She dies of grief, realizing that she will never meet him. Three years later, he sees a portrait of her, and cries out; his cries bring her back from the dead.

Across the world from each other, Tang and Monteverdi couldn't have conceived that they were writing their own cultures' versions of the same story in the same decade.

These are the connections I want to explore. All classical music is fair game, from a Sumerian hymn written four thousand years ago to the music still being written. It has become conventional wisdom of late that classical music is somehow dying. I'm not interested in classical music's death. Instead, I'm looking for the song of Orpheus, or cry of Liu, that will give classical music new life.

Labels:

China,

Early Music,

Opera

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)