My first day in Jinan, as my roommate took me on a tour of the city, he pointed out the large blue sculpture in the center of Quancheng Square. "All Chinese cities have them," he told me. The sculpture is a little bizarre, to say the least: two blue posts, seemingly made of fiberglass, which twist around a metallic globe in the center. In some ways, it's an exemplary giant Chinese public square sculpture. Based on just this picture, it isn't entirely clear what it is, or what it is meant to represent (other than Jinan's greatness that the city could build such a monument to itself). Although some of these sculptures are truly abstract, they tend to be abstractions of the square they sit in. But how do you represent a public square? In Jinan's case, it's pretty easy. 泉城广场 means "City of Springs Square," after one of Jinan's old names. Accordingly, you color the sculpture blue and show its components gushing from the ground to represent a spring. (Just try to ignore the fact that all but twelve of Jinan's 200 springs were paved over to build this square and its surrounding areas. Who needs a natural heritage when you have sculptures?)

My first day in Jinan, as my roommate took me on a tour of the city, he pointed out the large blue sculpture in the center of Quancheng Square. "All Chinese cities have them," he told me. The sculpture is a little bizarre, to say the least: two blue posts, seemingly made of fiberglass, which twist around a metallic globe in the center. In some ways, it's an exemplary giant Chinese public square sculpture. Based on just this picture, it isn't entirely clear what it is, or what it is meant to represent (other than Jinan's greatness that the city could build such a monument to itself). Although some of these sculptures are truly abstract, they tend to be abstractions of the square they sit in. But how do you represent a public square? In Jinan's case, it's pretty easy. 泉城广场 means "City of Springs Square," after one of Jinan's old names. Accordingly, you color the sculpture blue and show its components gushing from the ground to represent a spring. (Just try to ignore the fact that all but twelve of Jinan's 200 springs were paved over to build this square and its surrounding areas. Who needs a natural heritage when you have sculptures?)Most public squares in China, though, don't have names as evocative as "City of Springs."

How do you depict Civilization Square, for example? The solution used in this sculpture in Jiangyin, a small city in Jiangsu Province on the southern banks of the Yangtzi River, is to depict the word civilization itself. The Chinese word -- 文明 -- has two components. The 文 is unmistakable. (I'm not certain of this, but I believe that the version shown in the picture is in Chinese seal script.) 明 itself consists of two different characters: 日, meaning sun, and 月, meaning moon. Furthermore, texts in Chinese are traditionally can be written top to bottom. This sculpture is just the name of the square written large. (It is also a fitting sentiment for the front of the city government building. Google images has some other photos that give a good sense of its placement.)

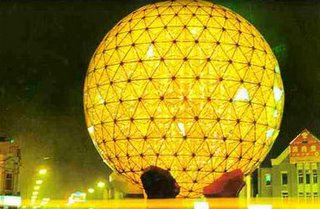

How do you depict Civilization Square, for example? The solution used in this sculpture in Jiangyin, a small city in Jiangsu Province on the southern banks of the Yangtzi River, is to depict the word civilization itself. The Chinese word -- 文明 -- has two components. The 文 is unmistakable. (I'm not certain of this, but I believe that the version shown in the picture is in Chinese seal script.) 明 itself consists of two different characters: 日, meaning sun, and 月, meaning moon. Furthermore, texts in Chinese are traditionally can be written top to bottom. This sculpture is just the name of the square written large. (It is also a fitting sentiment for the front of the city government building. Google images has some other photos that give a good sense of its placement.) Not all the sculptures are able to make such a connection, however. Dalian's Zhongshan Square, named after Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the founder of modern China, chooses a glowing orb as its centerpiece. The round sculpture is fitting for the center of Dalian's giant rotary at the center of the city. As you can see, at night, it lights up the square around it. (Or, at least the center of the square -- the edges of the square are lit up by the adjacent billboards and buildings.) However, it's hard to get excited about a sculpture whose chief influence is Epcot Center.

Not all the sculptures are able to make such a connection, however. Dalian's Zhongshan Square, named after Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the founder of modern China, chooses a glowing orb as its centerpiece. The round sculpture is fitting for the center of Dalian's giant rotary at the center of the city. As you can see, at night, it lights up the square around it. (Or, at least the center of the square -- the edges of the square are lit up by the adjacent billboards and buildings.) However, it's hard to get excited about a sculpture whose chief influence is Epcot Center.

Strange as it may sound, these are some of the normal ones. Consider the People's Square in Qinhuangdao. Legend has it, the great emporer Qin Shihuang went there seeking immortality. It is also the the point where the Great Wall reaches the sea. (More recently, it is the largest port in Hebei province since Tianjin left to become an independent municipality.) The square doesn't choose to explore the city's history, though, and the result is a very forgettable sculpture. There is little to distinguish it from its counterpart in People's Square in Linyi, a small city in southeastern Shandong Province. The Mayor of Linyi boasts of the city's heritage as the home of ancient manuscripts of Sun Tsu's Art of War and great figures from China's history. (Notice how the sculpture is used as the web sites

icon -- they are choosing it to be the symbol for the city.)

icon -- they are choosing it to be the symbol for the city.)What's the difference between these sculptures, though? They share the same Chinese red color, the same tripod structure, and the same jagged edges. An argument could be made that Qinhuangdao's version focuses itself inward, whereas Linyi's pushes outward, but that's a bit of a stretch. There is nothing to connect one to Qinhuangdao and the other to Linyi -- they could easily be swapped, and the cities would be no better or worse for it.

These sculptures are a uniqely Chinese phenomenon. I'd like to conclude with a picture of the mother of them all: the earliest such sculpture. This one is made of iron, in the far western city of Bali [巴黎, not to be confused with Bali in Indonesia]:

(See also photo supplement)

No comments:

Post a Comment