Like the Mongols of the twelfth century, today's bloggers have breached the Great Firewall. Which is to say, I discovered last night that China is allowing foreign blogs to be read (at least, at the moment). I may as well take advantage of this opportunity and try to write some more about China, for my readers over there. Coincidentally, there's something good to write about in the paper this morning:

The Times discusses the recent trend in Chinese art: selling your work for millions of yuan. At first glance, this would seem to aid the artistic process in China, but does it really?

The problem is that when the focus becomes economic, then the art suffers. This may not have been a concious strategy by the government to protect itself from satire, but it's working wonders by bringing these artists into the fold, and moving their focus to money. The question is no longer what Zhang Xiaogang [张晓刚] has to say about China during the Cultural Revolution; it's how many new versions of that same painting of the family of three his studio can churn out and sell. Who cares what Fang Lijun [方力钧] thinks about the post-Tiananmen world. How many paintings or sculptures of distorted faces can he finish in time for the next auction?

It's as if the artists of China are collectively turning from the Pollocks, Rothkos, and Warhols into many Thomas Kinkades, using "art" as a way to print money, expression be damned.

I realize that this is an overly bleak assessment; I look forward to a new generation of artists who will come shine some light on this problem by finding a way around it. I fear that it's too late for the current generation, though.

Showing posts with label Visual Art. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Visual Art. Show all posts

1.04.2007

12.30.2005

Behind the Great Firewall

I did something rare and difficult: I got my blog read in China (at least by one person). (See the proof here.) My friend Rena helped me gather some of the photos of some of the ugly Chinese sculptures, so I wanted her to see those entries. She's very intellegent and very open-minded (which is a rare quality in the people I met over there, so I feel like I actually can discuss things with her.

She pointed out two sculptures in Tiananmen Square, which have very famous within China. Of the first, Rena writes, "but that soldier sculptures are considered as one of the greatest sculptures after 1949 P.R. China set up in the text book." (Forgive her English, which, all things being equal, is actually very strong, though far from perfect.) As an outsider, it's hard to be enthusiastic about what is actually a pretty straightforward piece of propaganda, all content and no form. Yes, we get it, the communists were heroic and saved China. I don't really take anything from this sculpture, though, as art. There is a more interesting sculpture, across the street in front of Tiananmen proper. It is a marble pillar [华表], traditionally placed in front of palaces and tombs. When I reacted positively to the pillar, Rena had an interesting reaction:

anything from this sculpture, though, as art. There is a more interesting sculpture, across the street in front of Tiananmen proper. It is a marble pillar [华表], traditionally placed in front of palaces and tombs. When I reacted positively to the pillar, Rena had an interesting reaction:

She raises an interesting question: to what extent is it possible to retain a Chinese identity without just repeating the past again and again? Is it possible to incorporate Western ideas while still being Chinese?

This is actually a much greater issue, which has played out repeatedly throughout the history of music. American composers faced the same struggles with the influences of European music. Conventional wisdom has it that it wasn't until the turn of the 20th century that Charles Ives solved that problem (though I think people don't give William Billings full credit). Russia had its own conflict in the second half of the nineteenth century. (For that matter, look at the wave of nationalistic composers who felt compelled to assert their own countries' musical autonomies throughout the century.)

The problem is particularly strong in China, however, because of its history. From the end of the nineteenth through the first half of the twentieth century, there was a strong foreign presence in certain areas. Suddenly, after the revolution, that ended. The next twenty five years featured strict isolation, until foreign influences were gradually allowed again. The result is a country that today is still struggling to find a voice. (I'm glossing over a lot of issues for the sake of length, although those may come up in future posts.)

It's encouraging to talk to Rena and know that she struggles with these questions, as a young citizen of the country. It's not just up to the artists to find an identity.

She pointed out two sculptures in Tiananmen Square, which have very famous within China. Of the first, Rena writes, "but that soldier sculptures are considered as one of the greatest sculptures after 1949 P.R. China set up in the text book." (Forgive her English, which, all things being equal, is actually very strong, though far from perfect.) As an outsider, it's hard to be enthusiastic about what is actually a pretty straightforward piece of propaganda, all content and no form. Yes, we get it, the communists were heroic and saved China. I don't really take

I know foreigners always think these traditional things are much chinese. China is supposed to be like Xi'an

China should be full of old buildings with wing roofs

She raises an interesting question: to what extent is it possible to retain a Chinese identity without just repeating the past again and again? Is it possible to incorporate Western ideas while still being Chinese?

This is actually a much greater issue, which has played out repeatedly throughout the history of music. American composers faced the same struggles with the influences of European music. Conventional wisdom has it that it wasn't until the turn of the 20th century that Charles Ives solved that problem (though I think people don't give William Billings full credit). Russia had its own conflict in the second half of the nineteenth century. (For that matter, look at the wave of nationalistic composers who felt compelled to assert their own countries' musical autonomies throughout the century.)

The problem is particularly strong in China, however, because of its history. From the end of the nineteenth through the first half of the twentieth century, there was a strong foreign presence in certain areas. Suddenly, after the revolution, that ended. The next twenty five years featured strict isolation, until foreign influences were gradually allowed again. The result is a country that today is still struggling to find a voice. (I'm glossing over a lot of issues for the sake of length, although those may come up in future posts.)

It's encouraging to talk to Rena and know that she struggles with these questions, as a young citizen of the country. It's not just up to the artists to find an identity.

Labels:

China,

Visual Art

12.27.2005

The Art of the Public Square

My first day in Jinan, as my roommate took me on a tour of the city, he pointed out the large blue sculpture in the center of Quancheng Square. "All Chinese cities have them," he told me. The sculpture is a little bizarre, to say the least: two blue posts, seemingly made of fiberglass, which twist around a metallic globe in the center. In some ways, it's an exemplary giant Chinese public square sculpture. Based on just this picture, it isn't entirely clear what it is, or what it is meant to represent (other than Jinan's greatness that the city could build such a monument to itself). Although some of these sculptures are truly abstract, they tend to be abstractions of the square they sit in. But how do you represent a public square? In Jinan's case, it's pretty easy. 泉城广场 means "City of Springs Square," after one of Jinan's old names. Accordingly, you color the sculpture blue and show its components gushing from the ground to represent a spring. (Just try to ignore the fact that all but twelve of Jinan's 200 springs were paved over to build this square and its surrounding areas. Who needs a natural heritage when you have sculptures?)

My first day in Jinan, as my roommate took me on a tour of the city, he pointed out the large blue sculpture in the center of Quancheng Square. "All Chinese cities have them," he told me. The sculpture is a little bizarre, to say the least: two blue posts, seemingly made of fiberglass, which twist around a metallic globe in the center. In some ways, it's an exemplary giant Chinese public square sculpture. Based on just this picture, it isn't entirely clear what it is, or what it is meant to represent (other than Jinan's greatness that the city could build such a monument to itself). Although some of these sculptures are truly abstract, they tend to be abstractions of the square they sit in. But how do you represent a public square? In Jinan's case, it's pretty easy. 泉城广场 means "City of Springs Square," after one of Jinan's old names. Accordingly, you color the sculpture blue and show its components gushing from the ground to represent a spring. (Just try to ignore the fact that all but twelve of Jinan's 200 springs were paved over to build this square and its surrounding areas. Who needs a natural heritage when you have sculptures?)Most public squares in China, though, don't have names as evocative as "City of Springs."

How do you depict Civilization Square, for example? The solution used in this sculpture in Jiangyin, a small city in Jiangsu Province on the southern banks of the Yangtzi River, is to depict the word civilization itself. The Chinese word -- 文明 -- has two components. The 文 is unmistakable. (I'm not certain of this, but I believe that the version shown in the picture is in Chinese seal script.) 明 itself consists of two different characters: 日, meaning sun, and 月, meaning moon. Furthermore, texts in Chinese are traditionally can be written top to bottom. This sculpture is just the name of the square written large. (It is also a fitting sentiment for the front of the city government building. Google images has some other photos that give a good sense of its placement.)

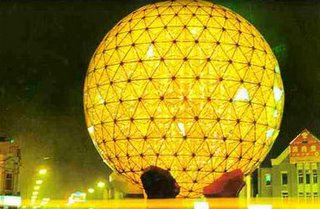

How do you depict Civilization Square, for example? The solution used in this sculpture in Jiangyin, a small city in Jiangsu Province on the southern banks of the Yangtzi River, is to depict the word civilization itself. The Chinese word -- 文明 -- has two components. The 文 is unmistakable. (I'm not certain of this, but I believe that the version shown in the picture is in Chinese seal script.) 明 itself consists of two different characters: 日, meaning sun, and 月, meaning moon. Furthermore, texts in Chinese are traditionally can be written top to bottom. This sculpture is just the name of the square written large. (It is also a fitting sentiment for the front of the city government building. Google images has some other photos that give a good sense of its placement.) Not all the sculptures are able to make such a connection, however. Dalian's Zhongshan Square, named after Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the founder of modern China, chooses a glowing orb as its centerpiece. The round sculpture is fitting for the center of Dalian's giant rotary at the center of the city. As you can see, at night, it lights up the square around it. (Or, at least the center of the square -- the edges of the square are lit up by the adjacent billboards and buildings.) However, it's hard to get excited about a sculpture whose chief influence is Epcot Center.

Not all the sculptures are able to make such a connection, however. Dalian's Zhongshan Square, named after Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the founder of modern China, chooses a glowing orb as its centerpiece. The round sculpture is fitting for the center of Dalian's giant rotary at the center of the city. As you can see, at night, it lights up the square around it. (Or, at least the center of the square -- the edges of the square are lit up by the adjacent billboards and buildings.) However, it's hard to get excited about a sculpture whose chief influence is Epcot Center.

Strange as it may sound, these are some of the normal ones. Consider the People's Square in Qinhuangdao. Legend has it, the great emporer Qin Shihuang went there seeking immortality. It is also the the point where the Great Wall reaches the sea. (More recently, it is the largest port in Hebei province since Tianjin left to become an independent municipality.) The square doesn't choose to explore the city's history, though, and the result is a very forgettable sculpture. There is little to distinguish it from its counterpart in People's Square in Linyi, a small city in southeastern Shandong Province. The Mayor of Linyi boasts of the city's heritage as the home of ancient manuscripts of Sun Tsu's Art of War and great figures from China's history. (Notice how the sculpture is used as the web sites

icon -- they are choosing it to be the symbol for the city.)

icon -- they are choosing it to be the symbol for the city.)What's the difference between these sculptures, though? They share the same Chinese red color, the same tripod structure, and the same jagged edges. An argument could be made that Qinhuangdao's version focuses itself inward, whereas Linyi's pushes outward, but that's a bit of a stretch. There is nothing to connect one to Qinhuangdao and the other to Linyi -- they could easily be swapped, and the cities would be no better or worse for it.

These sculptures are a uniqely Chinese phenomenon. I'd like to conclude with a picture of the mother of them all: the earliest such sculpture. This one is made of iron, in the far western city of Bali [巴黎, not to be confused with Bali in Indonesia]:

(See also photo supplement)

Labels:

China,

Visual Art

12.18.2005

NAMOC

One of the most interesting museums I visited in China was the National Art Museum of China (or NAMOC for short) [中国美术馆]. It offers a look at the last century of Chinese art. Needless to say, the twentieth century in China was one of great upheaval. That is reflected in the art.

One of the most interesting museums I visited in China was the National Art Museum of China (or NAMOC for short) [中国美术馆]. It offers a look at the last century of Chinese art. Needless to say, the twentieth century in China was one of great upheaval. That is reflected in the art.Yi Ming's [佚名] painting from 1928, is a good example of early Republican era art. In some ways it is two things at once -- it both fits in the tradition Chinese landscape painting and betrays European influences. Instead of the sparse Chinese textures, it is a full-scale oil painting. (The museum labels it as 仕 女肖像, which means "Portrait of Female Official." That is obviously not correct. You can see the actual female official here.)

As the civil war between the KMT and the CCP heated up, political themes became more

common. The struggles got worse with the invasion of Japan in 1937. "The Call of July 7" [“七七”的号角], painted by Tang Yihe [唐一禾] in 1940, depicts Chinese citizens marching to rebuff the Japanese. (This painting is very tame, actually. Take a look at the other paintings from the 1940's, which depict fighting, evacuations, and hunger.) The war, which didn't end until Japan surrendered to the US in 1945, is still a very current issue in Sino-Japanese relations. (It even has currency in the arts -- Bright Sheng, a Chinese composer now living in Michigan, wrote Nanking! Nanking!, a concerto about the Japanese occupation of Nanjing, in 1999.)

common. The struggles got worse with the invasion of Japan in 1937. "The Call of July 7" [“七七”的号角], painted by Tang Yihe [唐一禾] in 1940, depicts Chinese citizens marching to rebuff the Japanese. (This painting is very tame, actually. Take a look at the other paintings from the 1940's, which depict fighting, evacuations, and hunger.) The war, which didn't end until Japan surrendered to the US in 1945, is still a very current issue in Sino-Japanese relations. (It even has currency in the arts -- Bright Sheng, a Chinese composer now living in Michigan, wrote Nanking! Nanking!, a concerto about the Japanese occupation of Nanjing, in 1999.)After Mao declared the People's Republic in 1949, the tone of the paintings changed decidedly.

There was a resurgence of traditional style painting, consistent with the communist ideology's cultural

isolation. Naturally, there was also a surge in propaganda painting. The bucolic scene seems harmless enough, until you examine the iconography. Those peasant women, smiling as they plow the fields, are in traditional Tibetan dress. They are pleased because the enlightened Chinese occupying army has freed them from their own self rule. The painting's title? The First Step on the Golden Road [初踏黄金路]. Li Huanmin [ 李焕民] painted it in 1963, eleven years after Tibet was "liberated."

isolation. Naturally, there was also a surge in propaganda painting. The bucolic scene seems harmless enough, until you examine the iconography. Those peasant women, smiling as they plow the fields, are in traditional Tibetan dress. They are pleased because the enlightened Chinese occupying army has freed them from their own self rule. The painting's title? The First Step on the Golden Road [初踏黄金路]. Li Huanmin [ 李焕民] painted it in 1963, eleven years after Tibet was "liberated."Not all Chinese propoganda art is this cruel, however. Portraits of Mao were naturally quite popular, depicting him as a friend, a sage, an older brother, and, of course, as a wise leader. (These paintings still have currency in China today. Somehow, Mao has avoided the re-examination that brought Hitler and Stalin out of favor after they died.) My favorite of these is Sun Zixi's [孙滋溪] In Front of Tiananmen [前天安门], depicting a cross-section of Chinese citizens posing in front of the Gate of Heavenly Peace, China's national symbol. (The gate is across the street from Tiananmen Square, which has become infamous outside of China after the 1989 incident.)

The scene is one that is repeated hundreds (if not thousands) of times every day, as people from all over the country flock to see the monument that has been at the center of Chinese life for 500 years. In this painting, soldiers, officials, and peasants all stand together, along with people representing several of China's ethnic

The scene is one that is repeated hundreds (if not thousands) of times every day, as people from all over the country flock to see the monument that has been at the center of Chinese life for 500 years. In this painting, soldiers, officials, and peasants all stand together, along with people representing several of China's ethnic minorities. This is classical propoganda, showing the ideal society that communism (and Mao) have brought.

minorities. This is classical propoganda, showing the ideal society that communism (and Mao) have brought.The repressive Cultural Revolution years are conspicuously absent from the museum. The revolution sought to eliminate old customs, old habits, old thinking, and old culture. (That was communism at its worst.) Things started to open up then, however. Nixon visited and Deng Xiaoping instituted reforms, and Western influences returned to Chinese painting. There is little to suggest that this nude figure is a Chinese painting, or was painted in 1980. Jin Shangyi [靳尚谊] seems influenced by a classical Western sense of beauty. Likewise, Wei Qimei's [韦启美] New Wires [新 线 ] seems almost abstract (even though it depicts something very concrete -- large spools of electircal wire demonstrating China's modernization). The texture of the paint almost takes over from the images on the canvas.

I'm going to artificially stop this brief survey at 1983. At some point, I'll pick things back up and include a look at Shanghai's gallery, which has a better collection of contemporary art. Also planned is a look at contemporary Chinese classical music, which shares a similar trajectory as painting. Finally, I'll be doing the first assessment of an important genre of modern Chinese sculpture: the art of the Chinese public square.

For more on painting, check out the on-line collections of the National Art Museum of China and the Shanghai Art Museum. Don't be intimidated by the Chinese writing; just click around on things and have fun.

Labels:

China,

Visual Art

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)